April 13

“a little snow lying in some places. Martins appear. Mockingbird sings”

Reflections on Remembering Time and Place--

Thomas Jefferson in Annapolis, Maryland,

November 25, 1783-May 11, 1784

November 25, 1783-May 11, 1784

Thomas Jefferson / Charles Willson Peale, 1791/ Oil on canvas / Independence National Historical Park Collection, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

After Thomas Jefferson returned from his diplomatic mission to France in 1790 to become Secretary of State in Washington’s administration, Charles Willson Peale painted this portrait (1791-1792) displaying it in his Philadelphia Museum. By then much had changed, both in the government of the United States, and in the town of Annapolis that Jefferson had left on May 11, 1784 for his post in Paris.

One outstanding feature of the Annapolis landscape that was not there in 1783-84, when Jefferson lived in Annapolis, and attended Congress as a delegate from Virginia, was the magnificent wooden dome of the Maryland State House, said to be the largest of its kind in English speaking America.

After Congress moved the seat of the national government to Trenton, N.J. in November of 1784, having fled to Annapolis in the fall of 1783 from the angry uncompensated veterans in Philadelphia, the Maryland government decided to remove the old, leaky roof and dome of the Annapolis State House and replace it with something more grand and permanent as proposed and executed by a self-taught architect, Joseph Clark.

Charles Willson Peale, who got his start as an artist in Annapolis, sketched the results of the State House renovations in 1788.

From the vantage point of the walkway high up on the dome, in September 1790, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison would reflect with a friend on the stories that could be told of the town Jefferson had known so well in those nearly seven busy months in Annapolis. He lived first at Mrs. Ghiselin’s boarding house on West Street, and then in a house just off Church Circle, rented from the eminent non-juror and loyalist sympathizing lawyer Daniel Dulany. The foundation of the house is now under the Anne Arundel County Courthouse Annex.

On the trek up the narrow wooden stairway to the walkway around the dome, Jefferson was accompanied by James Madison, Thomas Lee Shippen, and Shippen’s friend, Dr. Schaaf, who for three hours regaled them by “opening the roofs of the houses, telling us the history of each family who lived in them.” The next day they had a sumptuous dinner of turtle and expensive old Madeira at George Mann’s Inn off Church (now Main Street) and Conduit.

Given the extent and quantity of his writing during his stay in Annapolis, it is difficult to imagine that Jefferson slept much. He found time to complete his Notes on Virginia which, because of the high cost of printing in America, he took with him to be published in Paris. He also composed position papers and recommendations on the currency, on the disposition of the lands in the Northwest Territory that had been won from Britain, on the finances of the struggling Confederation government, on the protocol for accepting George Washington’s resignation as Commander in Chief (which took place on December 23, 1783), and a remarkable series of notes and annotations on number of subjects given to a Dutch friend, G. K. von Hogendorp, who later published his memories of Jefferson’s habits in Annapolis:

Mr. Jefferson, during my attendance at the session of Congress, was more busily engaged than anyone. Retired from fashionable society, he concerned himself only with affairs of public interest, his sole diversion being that offered by belles lettres. The poor state of his health, he told me occasionally, was the cause of this retirement; but it seemed rather that his mind, accustomed to the unalloyed pleasure of the society of a lovable wife, was impervious since her loss to the feeble attractions of a common society, and that his soul, fed on noble thoughts, was revolted by idle chatter. [Boyd, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 7:82]

He even took time almost immediately on his arrival in Annapolis, to instruct his eleven year old daughter, Patsy, on how she should occupy her time in Philadelphia. On November 28, 1783, he wrote:

...the following is what I should approve.

from 8. to 10 o’clock practise music

from 10. to 1. dance one day and draw another

from 1. to 2. draw on the day you dance, and write a letter the next day.

from 3. to 4. read French.

from 4. to 5. exercise yourself in music

from 5. till bedtime read English, write &c.

...

I expect you will write to me by every post. Inform me what books you read, what tunes you learn, and inclose me your best copy of every lesson in drawing. [Boyd, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 7:360]

Jefferson also began to record the weather each day, beginning, perhaps as a new year's resolution, in January of 1784, a habit he continued with one interruption, through January of 1790, and his return from France to Monticello. [Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 771 ff].

He also recorded his daily expenses which provide the basic outline for what he was doing and purchasing while in Annapolis, including send his Hemings servant to Baltimore to become a hairdresser. It didn’t work out. Hemings refused to go to France, and returned with the horses to Monticello while Jefferson went on to France. Evidently from the Peale portrait, Jefferson ultimately chose to do little with his hair, unlike many of his contemporaries. [see: Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, ff 540-548].

He also recorded his daily expenses which provide the basic outline for what he was doing and purchasing while in Annapolis, including send his Hemings servant to Baltimore to become a hairdresser. It didn’t work out. Hemings refused to go to France, and returned with the horses to Monticello while Jefferson went on to France. Evidently from the Peale portrait, Jefferson ultimately chose to do little with his hair, unlike many of his contemporaries. [see: Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, ff 540-548].

On his birthday on April 13, 1784, Jefferson found the day fair and the temperature ranging from 45 to 58 degrees fahrenheit accompanied by the note: “a little snow lying in some places. Martins appear. Mockingbird sings.” [Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 773-774]

Nearly fifty years ago, I brashly set out to map and interpret the town of Jefferson and of Congress’s time in Annapolis. With the help of my mentor, Johns Hopkins history professor Jack Greene, who agreed to be nominal principal investigator because a lowly graduate student could never secure a research grant on such a scale, I wrote a successful grant proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities. The research files and the product of that research project are to be found at the Maryland State Archives. I have placed the maps and the lot histories on line.

My dream was to create a layer of space and time that would accurately explain who owned what and where people lived in Annapolis in 1783 and 1784. To do so, the project I directed pioneered in creating accurate base maps (derived from the Sanborn insurance maps) and plotted the history of every piece of property in town as we could document it for 1783-84, linking place to biographies of residents and visitors, particularly members of Congress and residents who appeared on the tax list of 1783. It was all done on paper without the aid of computers and Google Maps, inspired by the work on one street, Cornhill, undertaken by one of the most thoughtful, gifted, and dedicated Archivists I have had the privilege to know, Phebe Jacobsen and her husband Bryce Jacobsen, long time athletic director for St. Johns College. It would translate well into an on-going, dynamic research web site, if only a sponsor and funding could be found.

While the project never became the model for the on-going history of Annapolis that I had hoped it would, especially with the promise of the virtual world, it did inspire one of my colleagues, Jane McWilliams, to become the historian of the city. Her book on Annapolis is both definitive and a good read.

From our study of Annapolis lot histories, you can discover the places today that have survived, and that Jefferson would recognize, as well as learn of the sites of places no longer visible, where Jefferson dwelled, patronized, and was entertained.

To guide and to document Jefferson’s activities in Annapolis, Jefferson has left a detailed accounting record, as well as extensive correspondence which Julian Boyd has made so accessible and readable in book form, but not all of which is yet accessible on line.

If I were to lead a walking tour of Annapolis of places most familiar to Jefferson during his stay in 1783-84, I would start at the State House, in the rotunda, at the exhibit case containing the single piece of paper on which George Washington hastily (for him) composed his remarks to Congress resigning his commission, remarks that were required by the protocol of the ceremony Jefferson and his committee set forth for noon on December 23, 1783.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Maryland+State+House/@38.978828,-76.490974 |

Elaine Bachmann, Director of Artistic Property, Exhibits and Public Outreach, discusses the George Washington resignation display on Thursday. The Maryland State Archives acquired the speech in 2007 and put it on display

Source: http://www.capitalgazette.com/news/annapolis/ph-ac-cn-history-qa-20150224,0,1397067,full.story

When on public business, Jefferson spent a great deal of time in the Maryland State House, most likely in the committee room, just off the Old Senate Chamber which houses some of the new exhibits prepared by the Maryland State Archives for interpreting the State House. Missing is the panel designed for the first exhibits in that room in 1984 which documented the residences of the members of Congress in 1783-84, but in its place, the text of that exhibit can be found at: http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5200/sc5287/000009/000000/000007/unrestricted/committee.pdf. If you care to know where the rest of Congress lived while in Annapolis, you should start there.

From the State House, exit to the northward, down the steps toward Lawyer’s Mall and left around the circle towards towards the Shaw House (8 State Circle). This was home and shop of the cabinet maker John Shaw where Jefferson would have stopped to order the cabinetry recorded in his accounts. Shaw was in charge of the furnishings and maintenance of the State House at the time and had commissioned the very large U. S. Flag that flew over the State House while Congress was resident.

The original of the watercolor depicting the flag over the State House when Jefferson resided in town, can be seen at one of the stops along the walk, the Hammond Harwood House. I discovered the watercolor by chance one day on a self-guided tour of the house. At the time it was not interpreted nor widely known. I was stunned to see that the flag we had reconstructed for the first version of the Shaw flag from the receipts for cloth used, was in error (since corrected) and was overwhelmed by the beauty of the detail of what it depicted of the town about the time of Jefferson’s return in 1790.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/8+State+Cir,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.9784263,-76.4911445 |

The original of the watercolor depicting the flag over the State House when Jefferson resided in town, can be seen at one of the stops along the walk, the Hammond Harwood House. I discovered the watercolor by chance one day on a self-guided tour of the house. At the time it was not interpreted nor widely known. I was stunned to see that the flag we had reconstructed for the first version of the Shaw flag from the receipts for cloth used, was in error (since corrected) and was overwhelmed by the beauty of the detail of what it depicted of the town about the time of Jefferson’s return in 1790.

Jefferson so admired the architecture of the Hammond Harwood House on Maryland Avenue, that he sketched it in some detail:

Proceed from the Shaw House around State Circle to Maryland Avenue and on to the Hammond Harwood House for one of the best house tours in the city.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Hammond-Harwood+House/@38.9801688,-76.4872671 |

Afterwards return to the corner of Maryland Avenue and Prince George Street, walking southward towards the Harbor. On your left, just before East Street, stop at the Paca House to visit the house and the gardens.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/William+Paca+House+%26+Garden/@38.979625,-76.487891 |

There is no indication that Jefferson ever visited the Paca House or the much larger Brice House around the corner on East Street, but it is doubtful that he would have missed a chance to visit the garden, and he may even have spent time in the two houses that enjoy the view of the garden. The Brice House, facing on East Street, is the largest of the colonial mansion built in Annapolis, and, if open, is well worth the visit. The interior woodwork that dates back to just before Jefferson’s time in Annapolis is especially charming, including the mantle carved by an indentured servant named Mickey Mantle.

After leaving the Paca Garden and the Paca and Brice townhouses, proceed next down Prince George Street, again towards the harbor, stopping in front of 142 Prince George Street, Dr. James Murray’s house. Apart from his government colleagues and those who stayed with him at the Dulany House on the west side of town, Jefferson probably spent more time here with Dr. Murray than any other resident. He may have even showered there from water collected from the roof in a lead lined cistern and funneled through a ‘shower head.’ Dr. Murray was a great believer in the medical advantages of a cold shower.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/142+Prince+George+St,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.9785575 |

Source: http://annapolisinn.com/blog/

Farther on, when you get to Randall Street, turn right, and proceed to Middleton’s Tavern on the right facing Market Space. In 1783/84 it would have been occupied by Gilbert Middleton, and after Jefferson left, by John Randall, a Revolutionary War veteran and supplier of uniforms, who, as customs officer appointed by Washington in the 1790s used the building as the first Annapolis customs house under the new Federal Constitution.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Middleton+Tavern/@38.978177,-76.486914 |

There would have been a market there in Jefferson’s time, but closer to the traffic circle. To his right, on Market Space, Jefferson would have seen the impressive Wallace Davidson and Johnson building, only one portion of which still stands today on the corner of Fleet and Market Space (. On his first days in Annapolis, Jefferson would visit John Davidson’s store in this building and purchase several items, repeating himself on more than one occasion throughout his stay.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/26+Market+Space,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.9780022,-76.4876057 |

The surviving quarter of the building on the corner of Fleet Street is just beyond the second large chimney

If you pause at the corner of Fleet and Market Space, and look back up towards the State House, 10 Cornhill was occupied by the silversmith John Chalmers from whom Jefferson purchased a silver cover for an ivory book, martingal rings & buckle for his horse.

Next follow Market Space to Main Street, turning right and walking up Main, proceed to Conduit. Turn left on to Conduit, passing a colonial style building on the left which is now a Masonic lodge (162 Conduit Street).

Neither it nor the row houses beyond would have been there in Jefferson’s time. Instead he would have seen the courtyard and Mann’s Tavern where he first stayed in Annapolis, and dined with his friends after his trip up the State House dome. Mann’s is also where George Washington slept during his brief stay in Annapolis in December 1783, and where he probably composed his remarks resigning his commission, now on display in the State House.

Next follow Market Space to Main Street, turning right and walking up Main, proceed to Conduit. Turn left on to Conduit, passing a colonial style building on the left which is now a Masonic lodge (162 Conduit Street).

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/162+Conduit+St,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.977195,-76.4900537 |

Neither it nor the row houses beyond would have been there in Jefferson’s time. Instead he would have seen the courtyard and Mann’s Tavern where he first stayed in Annapolis, and dined with his friends after his trip up the State House dome. Mann’s is also where George Washington slept during his brief stay in Annapolis in December 1783, and where he probably composed his remarks resigning his commission, now on display in the State House.

At the corner of Duke of Gloucester Street turn right and walk up the street towards Church Circle, turning left towards the 1820s Anne Arundel County Courthouse, the site of the house that Jefferson rented, and where he completed the draft of his Notes on Virginia.

When he left Annapolis for Paris, Jefferson sold his possessions and his library there to future president James Monroe for 21 pounds 12 shillings and 8 pence.

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/8+Church+Cir,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.977864,-76.493167 |

When he left Annapolis for Paris, Jefferson sold his possessions and his library there to future president James Monroe for 21 pounds 12 shillings and 8 pence.

[Boyd, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 6:240]

Undoubtedly the house was also supplied with some furniture belonging to Daniel Dulany, possibly including Dulany’s desk on which he wrote the best known attack on the Stamp Act of 1765, and the losing arguments in the debate with Charles Carroll of Carrollton over the fee making powers of the last colonial governor, Sir Robert Eden.

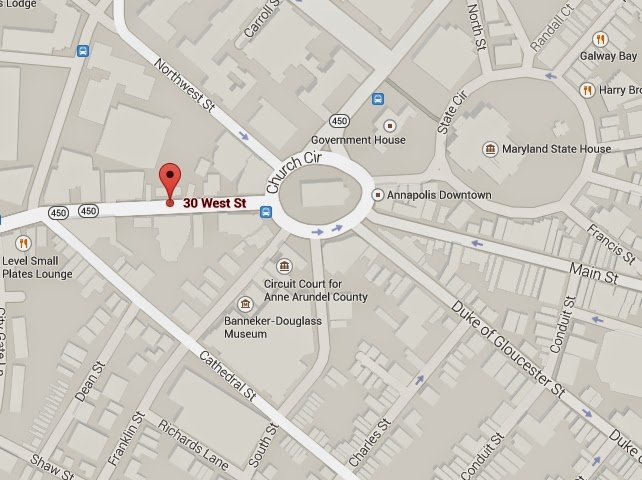

Continue around the outer rim of Church Circle past the Courthouse and by Reynold’s Tavern to West street, turning left. Pause at the site of Mrs. Ghesilin’s boarding house (30 West Street) where Jefferson first stayed on his arrival in Annapolis in November, 1783.

West Street was the approach by land to Annapolis in 1783. George Washington entered the city that way, as did Thomas Jefferson, although he would depart the city by the Rockhall Ferry in 1784. Turning back towards the Church on Church Circle, Jefferson would have seen a diminished pile of bricks for the new church (long since demolished and replaced by the current structure) from which an enterprising member of vestry (Thomas Hyde) ‘borrowed’ for his inn. The inn can still be seen at the tip of Main and Duke of Gloucester streets. Now known as the Maryland Inn, the first triangular shaped commercial building of its kind in America, it was still under construction in 1784.

|

|

| See: https://www.google.com/maps/place/30+West+St,+Annapolis,+MD+21401/@38.978379,-76.4944118 |

You might want to stop here for refreshment, or proceed back down Main Street to Middleton’s Tavern on Market Space.

It would have been here at Middleton’s Tavern that Jefferson would have purchased his passage on the Middleton ferry to Rock Hall when he left Annapolis on his way to Paris on May 11, 1784. His last entry for the weather in Annapolis was for the 10th of May when it was a pleasant 65 degrees. He would not resume his systematic recording of the weather until slightly over a year later in France, when on the afternoon of June 9, 1785, it was but a degree warmer.

It would have been here at Middleton’s Tavern that Jefferson would have purchased his passage on the Middleton ferry to Rock Hall when he left Annapolis on his way to Paris on May 11, 1784. His last entry for the weather in Annapolis was for the 10th of May when it was a pleasant 65 degrees. He would not resume his systematic recording of the weather until slightly over a year later in France, when on the afternoon of June 9, 1785, it was but a degree warmer.

If Jefferson celebrated his birthday while in Annapolis, no record of it survives. Happy Birthday, Mr. President! We should observe the day as a tribute to your public service and unceasing intellectual curiosity, even if you did not.

April 13, 2015